He made his fortune on cheap paperback novels. He was a Pictou County boy who lived in New York City and was never a student nor even an administrator or faculty member of Â鶹´«Ă˝. Yet his contribution to Dal was so great that, at one point, he was dubbed “Â鶹´«Ă˝â€™s second founder.”

But you probably know George Munro best for the holiday that, for nearly 140 years, has worn his name.

This Friday, February 7 Â鶹´«Ă˝ celebrates its annual Munro Day — a university-wide day off on the first Friday of February, welcomed by all those seeking a short break in the middle of winter.

It hasn’t always been in the middle of winter, though. At various points in Dal’s history, the holiday has been in mid-March or even in November at one point. But that’s not the only way modern Munro Days are a bit different than Munro Days past. Aside from having a slightly more cumbersome moniker in its early days — “George Munro Memorial Day,” so named even though its namesake was still alive at the time (he died in 1896) — activities like sleigh ride sing-alongs, formal dances and variety shows might all seem a bit antiquated to today’s students.

But whether you celebrate by skiing, sleeping in or anything else in between, Munro Day is a day for Dal students, faculty and staff to make their own. And the reason you get to do so is because of how one person chose to step in and save a fledgling young university in his home province — one he never even went to.

Munro made a big fortune on small books

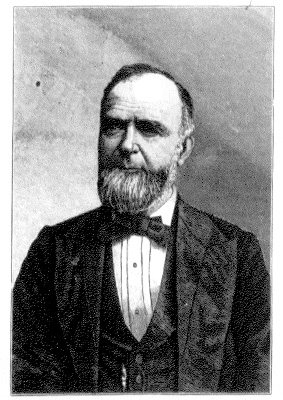

Born on November 12, 1825 in Pictou County, Nova Scotia, George Munro grew up with two possible paths ahead of him. One was in publishing, as he’d spent some time in his youth working at the Pictou Observer and taken an interest in the field. The other was education, as he taught for a time at Pictou Academy and at Free Church Academy in Halifax. (He’d also considered entering the Presbyterian ministry, but according to rumour he “preached one sermon and made a solemn vow never to renew the ordeal.”)

Munro chose publishing, moving to New York City and ending up at Appleton’s, a large publishing firm. He arrived just as a huge boom was starting in what would become known as “dime novels” — cheap, paperbound publications of popular fiction, often serialized, and sold at a price the masses could afford.

Munro chose publishing, moving to New York City and ending up at Appleton’s, a large publishing firm. He arrived just as a huge boom was starting in what would become known as “dime novels” — cheap, paperbound publications of popular fiction, often serialized, and sold at a price the masses could afford.

He soon found himself working for Irwin P. Beadle and Company, a purveyor in the field, and proved so successful that he soon was co-owning the company with Mr. Beadle himself. His imprints included Munro’s Ten Cent Novels and the immensely successful Seaside Library, which published more than 2,500 popular titles.

Munro earned enough money to even begin dabbling in New York real estate. His first modern apartment house, which faced Central Park, was named “Â鶹´«Ă˝.”

Munro funded a chair in physics when Dal was at risk of shutting its doors

So why would Munro name a building after Â鶹´«Ă˝? And how did a man with no formal affiliation with the university go on to become its holiday’s namesake?

Munro’s initial connection to Â鶹´«Ă˝ came through his brother-in-law, the Reverend John Forrest, who served on the Board of Governors in the 1870s and would later go on to become the Dal’s third president. (Carleton Campus’s Forrest Building, the original home of the university in Halifax’s south end, is named after him.) Given Munro’s continued interest in and enthusiasm for education, he was always keen to keep up with his home province’s fledgling new university, and would check in with Forrest on how it was going.

In the 1870s, it was not going great.

Â鶹´«Ă˝'s original campus on the Grand Parade in Halifax.

"Desperate is not too strong a word for Â鶹´«Ă˝'s financial condition,” writes Dal historian P.B. Waite in his book The Lives of Â鶹´«Ă˝. “Talk of closing Â鶹´«Ă˝ down was heard on every side." The school’s government grant was set to expire, and investment income wasn’t generating much revenue. For the second time in 30 years, it looked like Â鶹´«Ă˝â€™s doors might be closing.

In 1879, Forrest was talking with Munro about Dal’s plight, highlighting funds for an academic chair in physics as the biggest need. Munro’s response: “If you will find the man . . . I will find the money.”

The man was J.G. MacGregor, and the money was $2,000 per year — a rather large sum at the time, especially in the early days of higher education in Canada. And it was enough to keep Â鶹´«Ă˝ going.

But Munro was just getting started.

Munro's donations to Dal totalled $10M+ in today's funds

In the years to come, Munro would endow chairs in English Literature, in History, and in Rhetoric, Law and Philosophy. (The first Munro Professor of History: Rev. Forrest — less an act of nepotism, one assumes, than a reflection of Halifax’s intimate talent pool at the time.)

In addition to funding academic chairs, Munro donated some $83,000 in bursaries, some of which went to support some of Dal’s first female graduates.

All told, Munro donated about $330,000 to the university — a number which may seem small compared to the sorts of multi-million major donations universities like Dal can sometimes receive today, but given the time and context was cause for great celebration. Given inflation, that would be equivalent to more than $10 million today.

All told, Munro donated about $330,000 to the university — a number which may seem small compared to the sorts of multi-million major donations universities like Dal can sometimes receive today, but given the time and context was cause for great celebration. Given inflation, that would be equivalent to more than $10 million today.

Dal’s Board at the time described in “on a scale that is without parallel in the educational history not of Nova Scotia alone but of the Dominion of Canada.” Principal George Grant of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont.— a man with roots in Halifax who had served on Dal’s Board — wrote in a letter, “Munro must be going to die. Evidently he is too good for this world. His first gift saved Â鶹´«Ă˝. His second will turn the tide of ambitious students that was settling in to the larger institutions up here [in Ontario] and make it flow to Â鶹´«Ă˝.

“A mural crown he should have!”

A crown wouldn't be Munro's style. As Dr. William D. Forrest would later write of Munro, "He was a man of quiet, unassuming character, reserved almost to the point of shyness. He had no desire to bask in the sunshine of full recognition. Honorary degrees, complementary banquets and the like had no appeal for him.

“His gifts to Â鶹´«Ă˝ were prompted solely through patriotic ideals, his love for the land of his birth and his great interest in the cause of education in these Maritimes Provinces of Canada.”

Students gave Munro (and Dal) his day

So no, Munro didn’t get a crown. But he did get a holiday.

The idea for Munro Day came not from the Board, or the faculty, but from Dal’s students, who in the summer of 1881 brought forward a petition asking for university holiday to honour Munro’s generosity. The Board agreed, and “George Munro Memorial Day” was born.

In the 1880s, the highlight of the day’s events was a nine-mile sleigh ride to a Bedford hotel for a fancy dinner. In 1883, the Â鶹´«Ă˝ Gazette reported more than 50 students and profs took part in the event, out of a total school enrolment of 66.

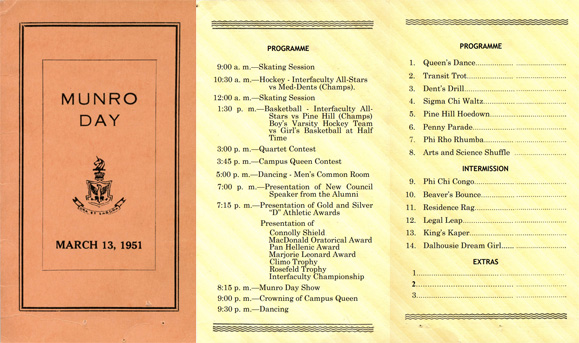

Through the years, as Munro Day (as it shortened to in 1928) has had many different activities. In the mid-20th century often the entire day was full of programming. A look back through in the Â鶹´«Ă˝ Archives shows activities like varsity games, musical performances, ice skating, awards presentations and, often, concluding with a dance — complete with dance cards full of cheeky Â鶹´«Ă˝-named dances.

Munro Day program, March 1951.

There’s not quite so much official programming on Munro Day these days, though student-organized ski trips remain a common activity. (Musical performances, too, seem to be having a comeback — in a manner of speaking.)

Still regardless of whether you’re spending the day — having fun, relaxing or perhaps even volunteering or giving back in Munro’s spirit — here's hoping all at Â鶹´«Ă˝ have a rewarding, refreshing Munro Day.

Watch: