The first time Bart Vautour attended a Major League Baseball (MLB) game, it was a big deal.

He was a small-town Canadian kid who’d grown up in the heart of the Toronto Blue Jays’ golden years, which culminated in the team bringing the World Series championship north of the border in back-to-back seasons. Baseball had been a bonding experience with his mother — a fandom they could share together. Now in his early 20s, he finally had the chance to take his outfield seat in the Skydome and experience the spectacle of the sport in person.

“And I was made immediately uncomfortable by people around me talking about the outfielder’s mother in explicitly misogynist ways,” he explains.

Flash forward a couple decades to 2023 and Dr. Vautour ‚ÄîÃ˝now a faculty member in Dal‚Äôs Department of English ‚Äî is back at the ‚Äòdome, now known as the Rogers Centre, for an otherwise ordinary early-season contest. Except in the one way it is not: Blue Jays player Anthony Bass enters the game as a relief pitcher for the first time since coming under fire for an Instagram post featuring an anti-2SLGBTQIA+ message. And he‚Äôs met with a thunderous chorus of boos ‚ÄîÃ˝perhaps not from everyone in the stadium, but certainly most of it. (Bass was gone from the team a few days later.)

Flash forward a couple decades to 2023 and Dr. Vautour ‚ÄîÃ˝now a faculty member in Dal‚Äôs Department of English ‚Äî is back at the ‚Äòdome, now known as the Rogers Centre, for an otherwise ordinary early-season contest. Except in the one way it is not: Blue Jays player Anthony Bass enters the game as a relief pitcher for the first time since coming under fire for an Instagram post featuring an anti-2SLGBTQIA+ message. And he‚Äôs met with a thunderous chorus of boos ‚ÄîÃ˝perhaps not from everyone in the stadium, but certainly most of it. (Bass was gone from the team a few days later.)

“You couldn’t help but feel that, palpably, baseball had changed,” says Dr. Vautour.

Baseball as text

Baseball is always changing. And it’s also constant.

As the MLB postseason gets underway this October ‚ÄîÃ˝the Blue Jays competing against the Minnesota Twins in a wild card series [Author's addendum, Oct 5: Well, that didn't go great] ‚ÄîÃ˝both sides of that equation are on full display. This is the first year that MLB has incorporated a pitch clock, bringing time into (as it‚Äôs infamously dubbed) America‚Äôs pastime like never before. (Games were, on average, 30 minutes shorter this year than they were last season.) This particular round of the playoffs the Jays find themselves in didn‚Äôt even exist until 2022. And the players on the field are more international than ever before, bringing new attitudes and approaches into both the personality and play of the game.

Toronto Blue Jays shortshop Bo Bichette makes a tag play.

Ã˝

But the elements that have made baseball the focus of so many wordy novels, heartfelt films and haughty documentaries ‚ÄîÃ˝they‚Äôre all still there. It remains a game that doesn‚Äôt just embrace its history but often venerates it (for good or ill), and where the consistency of action and play allows for records and statistics to be compared across generations.

“Baseball is very textual, both in its complicated rules and in being highly structured,” says Dr. Vautour. “It’s not so different, to me, than a sonnet — which is poetry working as a form and within constraints. The form and the rules can change over time, but it remains a consistent thing into which stories can be placed.”

Connecting culture

Those stories are at the core of the Sports Literature course Dr. Vautour is teaching this semester. It‚Äôs all about baseball ‚ÄîÃ˝how it‚Äôs represented in literature and in culture, in narratives we read or watch and in narratives that flow around it in our broader society.

‚ÄúSome of my students have played baseball all of their lives and are deeply steeped in the game, while others just took the course because it was the English class that fit their schedule ‚ÄîÃ˝and I‚Äôm really excited about both perspectives,‚Äù he explains.

‚ÄúI hope those who are already into baseball get to better appreciate the things that happen around it that can‚Äôt be ignored, that we need to talk about, while others will get to see how baseball ‚ÄîÃ˝like other activities in society ‚ÄîÃ˝can be a space around which other things circulate, how it can be a mirror at moments to talk about political, cultural and social representations.‚Äù

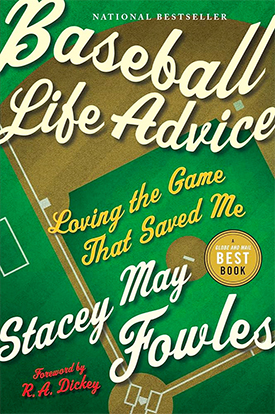

The course‚Äôs reading material includes American author Chad Harbach‚Äôs 2011 novel The Art of Fielding ‚ÄîÃ˝a story, appropriately for a university course, about college baseball ‚ÄîÃ˝but otherwise Dr. Vautour has tried to bring a particularly Canadian perspective to the syllabus, taking advantage of the game‚Äôs less-mythologized role in Canadian consciousness. For example, there‚Äôs Stacey May Fowles‚Äôs Baseball Life Advice ‚ÄîÃ˝an essay collection that explores, among other topics, the intersection between baseball and identity.

The course‚Äôs reading material includes American author Chad Harbach‚Äôs 2011 novel The Art of Fielding ‚ÄîÃ˝a story, appropriately for a university course, about college baseball ‚ÄîÃ˝but otherwise Dr. Vautour has tried to bring a particularly Canadian perspective to the syllabus, taking advantage of the game‚Äôs less-mythologized role in Canadian consciousness. For example, there‚Äôs Stacey May Fowles‚Äôs Baseball Life Advice ‚ÄîÃ˝an essay collection that explores, among other topics, the intersection between baseball and identity.

‚ÄúShe writes how everything about the sport makes her fandom uncanny ‚ÄîÃ˝because as a woman who‚Äôs an engaged baseball fan, you‚Äôre constantly reminded that you only belong in some aspects of the game. It shows how fandom has evolved to incorporate different levels of critical thought ‚ÄîÃ˝how we can cheer but also be critical of structures and biases. How do we negotiate fandom in our own time?‚Äù

Better baseball

For Dr. Vautour, personally, that fandom has changed a lot over the years. He finds himself listening to games more on the radio now rather than watching them on TV;Ã˝it‚Äôs easier to fit into his family life that way. He appreciates the companionship elements of baseball ‚ÄîÃ˝how it‚Äôs always there during the season but doesn‚Äôt demand you pay attention to all of it. Like many fans, there are elements of the big-budget corporate game he struggles with.Ã˝But he also tries to remember that baseball isn‚Äôt just MLB.

“Baseball is bigger than one league, and we — as fans of baseball — can demand something of that league, because we can demand it of baseball in general. And we can start by making baseball as inclusive as possible on our own playgrounds and ball fields, so that we expect it as we turn on our TVs as well.”

And while he’s cheering for the Blue Jays this October, he’s also just generally looking forward to some quality baseball.

“If the Blue Jays lose, and it was a good game, I’m honestly just as happy as if they’d won. I’m a fan of both baseball and the Blue Jays.”