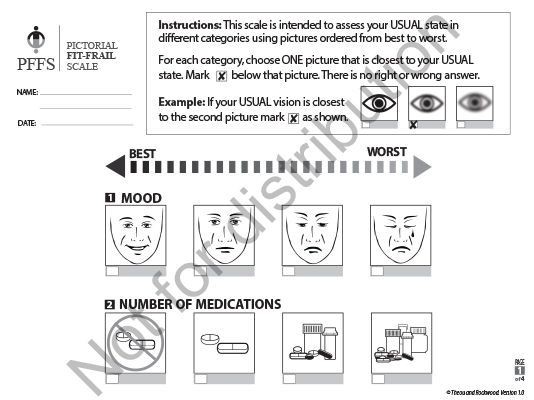

Pictorial Fit‑Frail Scale

��

The Pictorial Fit-Frail Scale (PFFS) uses simple visual images to assess a person’s level of fitness-frailty. There are versions of the PFFS which allow for assessment of a person’s usual state of fitness-frailty and there are versions of the PFFS which allow for assessment of both their usual and current (acute) states. Knowing the difference between how someone presents, for example, in the emergency department (their acute state) and what they were like approximately two weeks ago (their usual or pre-acute state) gives an indication of how these states differ and what the care goals of acute treatment may be.��

The PFFS assessment can be completed by an individual (self-assessment), a care partner (proxy-assessment), or a healthcare professional (clinical assessment). It is quick to administer, taking less than 2 minutes when assessed by a clinican and less than 5 minutes for self and proxy assessment. The PFFS evaluates a person's ability in 14 different domains. Within each domain, 3 to 6 levels of ability are represented with images and the assessor picks the image that best represents the usual state of the person being assessed. Images make the scale accessible across literacy levels, languages, and cultures. The PFFS visually shows change from one level to another and can facilitate discussion with the patient, and within the care team and their family. The PFFS is comprehensive and captures the multidimensionality of frailty.

There are currently four versions of the PFFS:

1) ��[PDF - 1.9MB]: for self- or proxy-assessment of a person's usual state of fitness-frailty.��

2) *��[PDF - 1.8MB]: for clinical assessment (by a health care professional) of a patient's usual state of fitness-frailty.

3) ��[PDF - 2.0MB]: for self- or proxy-assessment of a patient's current (acute) and usual state of fitness-frailty.��

4) *��[PDF - 1.8MB]: for clinical assessment of a patient's current (acute) and usual state of fitness-frailty.

*The HCP versions of the PFFS contain the same content as their non-HCP counterparts, however they contain fewer instructions and have been sized to fit on two pages instead of four.

��

PFFS Video Guide

��

Scoring the PFFS

For each domain, the level representing least or no impairment (first picture on the left) is scored 0, the next level (second picture from the left) as 1, etc. The minimum score for each domain is 0; the maximum score for each domain ranges from 2 to 5. Total PFFS scores are calculated by summing the scores across domains. The final summed score could theoretically range from 0 (no frailty; very fit) to 43 (severely frail). We encourage using the continuous PFFS score. Until further testing is complete, we recommend not calculating PFFS scores for individuals missing 4 or more domains.��

To facilitate comparison with other studies that measure frailty, PFFS scores can be transformed into frailty index scores by dividing the total PFFS score (the numerator) by the maximum theoretical score for the answered domains (the denominator). For example, an individual who answered all domains would have their PFFS score divided by 43. If the “aggression” domain is missing then their score would be divided by 41; if both “aggression” and “mobility” are missing then divide by 36, and so on. ��

��

Selected References:

Theou O, Andrew M, Ahip SS, Squires E, McGarrigle L, Blodgett JM, Goldstein J, Hominick K, Godin J, Hougan G, Armstrong JJ, Wallace L, Sazlina SG, Moorhouse P, Fay S, Visvanathan R, Rockwood K. ��Can Geriatr J. 2019;22(2):64-74. doi:10.5770/cgj.22.357

McGarrigle L, Squires E, Wallace LMK, Godin J, Gorman M, Rockwood K, Theou O. ��Age and Ageing. 2019;48(6):832-837. doi:10.1093/ageing/afz111

Wallace LMK, McGarrigle L, Rockwood K, Andrew MK, Theou O. International Psychogeriatrics. 2020;32(9):1063-1072. doi:10.1017/S1041610219000905

Ahip SS, Shariff-Ghazali S, Lukas S, Samad AA, Mustapha UK, Theou O, Visvanathan R.����[published online ahead of print, 2021 May 27].��Malaysian Family Physician. 2021;16(2). doi:10.51866/oa1036

Ysea-Hill O, Sani TN, Nasr LA, Gomez CJ, Ganta N, Sikandar S, Theou O, Ruiz JG. . Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine. 2021;7:1-7. doi:10.1177/23337214211003804

Cooper L, Deeb A, Dezube AR, Mazzola E, Dumontier C, Bader AM, Theou O, Jaklitsch MT, Frain LN. . Annals of Surgery. 2022; Epub ahead of print.��doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005381

��

Translations

The PFFS has been translated, with permission, into various languages by interested clinicians, researchers and organizations that are not directly affiliated with Geriatric Medicine Research. We have not independently translated, certified translation nor validated the tools in any of these languages.��

Watermarked previews of the currently available translations can be viewed on the Translations page.�� ��

��

Permission for Use

To guard against copyright infringement or unlicensed commercial use, we ask all potential users to complete a��Permission for Use Agreement via the��online��Permission Request Portal.��Agreements are reviewed by the Industry Liaison Office at �鶹��ý to determine whether a license agreement is required. Requests for non-commercial educational, clinical and research use, as well as for reprint usually do not require a license agreement.